The first time I saw a live pig was in 1976, when I was working for a trading company for a large Brazilian retail group. We had placed a chicken export sector in this trading company and the success led our president, who was more aggressive than a German panzer division, to expand into pork. The giant retailer opened its doors easily with its suppliers and this allowed me to get to know farms and slaughterhouses.

At the time, there was an incipient but attractive export of pork meat, a celebration that lasted until 1978, when an ASF episode in Brazil and it was communicated to the OIE. Immediately the doors closed in Brazil. My president at Pao de Acucar Trading, from whom I learned a lot and to whom I owe a lot, regretted it for a nanosecond (and in those days we did not have that measure of time) and asked me if I was in a position to leave immediately to visit external clients.

Astounded, I asked what the merit of the trip was, since we were banned, and he without hesitation said that that was why he should travel to find out what the customers intended to do, where they were going to buy from, and that the visit at the worst moment for the Brazilian exporter would show that we had coming to that market to stay.

I found that the problem was mutual, and we maintained our link with the import market with operations to Hong Kong, European ship chandlers and supply of construction sites for Brazilian contractors in some African countries.

In 1981, the OIE declared the episode over, and at that time we began to experience the taste of protectionism, with some countries reacting with the traditional “yes, but …”. And forgive me for repeating my mantra that “Brazil is a powerhouse in agribusiness located in a country that does not count internationally”, which gives the protectionists on duty the possibility of doing so with total peace of mind and without fear of fair retaliation.

The “yes, but …” caused our exports to falter in less than one hundred thousand tons and concentrated in very few countries for a decade and a half. Note in Graph I that it was only with the end of the Soviet Union that we broke this barrier, thanks to imports of pork carcasses by Russia.

At the time, I was still at the front, managing exports for a large Brazilian company. I alerted colleagues and principals that the Russian market would be an excellent market of opportunity, but not a perennial one, as it was Russia’s state policy to ensure self-sufficiency in the main meat consumed by Russians, pork.

But even in large companies, the verse of Cervantes prevails: “don’t wake me up if I’m dreaming”. I continued to hear the praises of Russian imports while I celebrated the opening of each new market with the same enthusiasm as the first chicken sale I made abroad in 1976.

Russia manages to restore its pork production to the levels of ensuring the supply of its people and becomes an occasional importer of specific products. But the opening of new markets and the expansion of traditional ones led Brazilian exports to be between five hundred and seven hundred thousand tons per year (cf. Graph I, 2002 to 2018).

Graph I – – Brazilian Pork Exports – Volume in kt

But then Planet China appears for Brazilian pig farming, followed by Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Georgia, Angola and the United States, not forgetting our neighbors Argentina, Chile and Uruguay. And Brazilian exports break the barrier of seven hundred thousand tons from 2019 with the ASF episodes in Asia.

China resumes in the first half of 2021 the levels of its pig herd and its pork production, but the expansion of markets allows Brazil to remain in the last three years with exports above one million tons per year. Addendum that great producing and consuming powers tend to maintain their imports, since each market values some type of cut or product.

If you ask the Italian market how they wanted each pig, they would answer that preferably with ten legs. The Spanish and Portuguese will answer the same, but with the caveat that all pigs must have acorns (“bellota”) as a differential part of their diet, while in the North American market they will ask for a pig with several bellies. And when visiting Italy, indulge yourself with a beautiful “prosciutto di Parma”; a “jamon bellota pata negra”, one of the thousand delights of Spanish gastronomy and, before my Portuguese friends turn against me, with a “black pork ham” (presunto de porco preto ou ibérico), one of the thousand and one wonders of Portuguese cuisine. And in the United States you will easily understand why Americans eat so much bacon once you have tasted it.

The result of these new markets, along with those who have always been with us, is that in the last three years the country’s exports reached a level of more than one million tons.

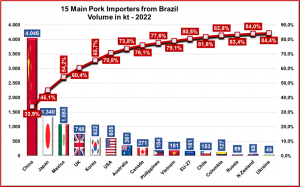

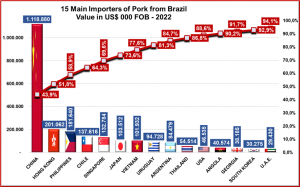

In Graphs II and III we can see that the fifteen main importers absorb more than 90% of Brazilian exports both in volume and in value, with the four largest importers accounting for 2/3 of total exports in 2022.

Graph II – Brazil- Volume of Pork Exports – 15 Main Importers in 2022 (t)

Graph III – Brazil- Value of Pork Exports – 15 Main Importers in 2022 (US$ 000)

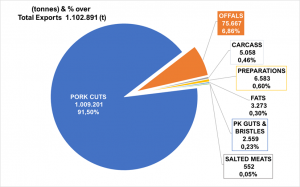

And what did Brazil sell to these 126 countries in 2022 in terms of pork and pork products? Predominantly, pork cuts and offals stood out due to demand from the main destination for Brazilian exports, Asia, which today accounts for >55% of world imports and for 53.4% of volumes exported by Brazil.

Graph IV – Brazil- Composition of Pork Exports by Category of Products in 2022

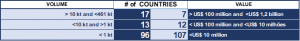

It is undoubtedly a high level of concentration, but on the other hand there are improvements. In 2022, Brazil exported to 126 countries in the world (cf. Table I), and even among those with minimal imports some of the biggest importing powers appear, such as Mexico and the United Kingdom, not to mention that Brazilian exports to Japan and the United States are in their infancy with potential for expansion.

Table I – Brazil – Pork Exports – Number of Importing Countries by Volume

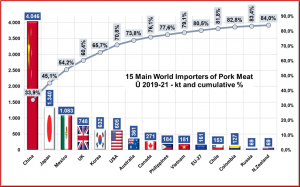

Verify that these importing powers arise when we verify the imported average 2019-2021 (cf. Graph IV), and most of the same countries have swine meat import projections for the next few years. The atypicality caused by the FSA in Asia between 2018 and 2020 means that we must wait longer before we can make projections without deviations from those currently available, where China emerges by 2023 with volumes ranging from 2.6 to 5.0 million tons.

These same projections quantify Brazilian exports from a modest 700 kilotons to a generous 1,400 kt. Do not wish badly to everyone who makes projections, but the formulas of Dr.Excel consider binary or statistical history. To a client who pondered that the projections are not always correct, I replied that we always hit the trends and that it is not ideal for navigation using GPS, trends are a better alternative than navigating blind.

Are we blind to this collection of data outside the curve? No, we know that Asia is the center of demand, and we know that pork production, trade and consumption will grow in the coming decade.

Graph V – Pareto – 15 Main World Importers of Pork Meat Ū 2019-21

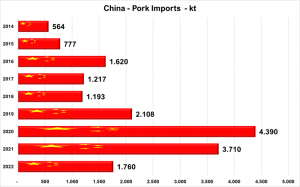

As China currently accounts for 1/3 of world pork imports, it is useful to study the recent history of Chinese imports

Graphic VI – Chinese Pork Imports – 2014-2022

We do not yet have data on Chinese pork imports in January and February 2023, but the latest FAS/USDA report indicates that these should grow by 4% this year. I also agree in saying that they will neither be at the record level of 2020, nor will they regress to the situation prior to the episodes of animal diseases. The COVID-19 outbreaks are under control and the movement of people in large urban centers is back to normal, which could contribute to the growth in demand.

As for Brazil, under normal conditions, I see a 2023 that pursues to reach or even surpass 1.2 million tons of exports. The first two months of this year experienced growth compared to 2022 of 14.9% in volume and 24.9% in export value.

It’s a good start, but anyone involved in agriculture knows that the only guarantee we have is when we buy a machine, a car or an appliance. There are so many variables that affect our activity, ranging from the weather to international events, most of which are beyond our control, not to mention romantic views on food production, suited to the 19th century, when the world population did not reach one billion people.

They agree that many times we must fight against the Fifth Column[1]. And those who spent or spend their lives in Brazilian agribusiness know that many times our biggest enemies are not external. But we also know the depth of verses of a popular Brazilian song by Paulo Vanzolini, MD and doctor in zoology from Harvard, scientist and poet.

A man of morals, Doesn’t stay on the floor…

Recognize the fall, But doesn’t become discouraged

He get up, shake off the dust

And carry on!

We in agribusiness too. But rest assured, My Dear Protectionists, because around here there are people who will continue to help you a lot.

[1] Fifth column is an expression used to refer to groups that act, within a country, helping the enemy. The expression was born during the Spanish Civil War and its creator would have been a general who advanced on Madrid with four columns. Interviewed by journalists, the general allegedly declared that he expected to win because, in addition to those four columns, he had a fifth – Franco supporters infiltrated the Madrid community